Iran’s National Operating System: A Two-Decade Analysis

The "National Operating System" project stands as one of the most ambitious initiatives in Iran's technological history. Launched over two decades ago with strategic goals ...

The "National Operating System" project stands as one of the most ambitious initiatives in Iran's technological history. Launched over two decades ago with strategic goals such as achieving digital independence and breaking the monopoly of foreign software, it was later integrated into the broader puzzle of the National Information Network. Despite significant investments and continuous efforts, the project's outcomes fell short of its lofty objectives and never reached fruition. This report delves into the twenty-year journey of this endeavor, analyzing its highs and lows.

The Grand Vision of Digital Independence

It all began in the late 1990s with growing concerns about dependency on foreign software. At a time when personal computers were rapidly gaining popularity, Windows dominated 97% of Iran’s market, sparking worries among policymakers. In response, in 2000, Iran's High Council for Informatics collaborated with Sharif University’s Advanced Information Technology Center to officially launch the National Operating System project.

According to Mohammad Sepehri Rad, then-secretary of the council, the initiative was driven by two primary factors: national security and global trade. He explained that "the resources for this operating system [Windows] are not under our control," exposing users to potential data breaches by "malicious actors." Economically, as discussions around Iran joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) gained traction, the country faced mounting pressure to pay licensing fees for millions of copies of foreign software, a stark departure from years of free duplication.

The solution proposed was to develop an indigenous operating system based on open-source Linux. Inspired by Richard Stallman’s free software philosophy and GNU Project principles, the endeavor secured an initial budget of 4 billion tomans. Majid Saeedi, who led Linux localization efforts at the time, outlined an ambitious goal: replacing Windows entirely by 2005.

From Unified Vision to Fragmented Reality

As work commenced on the project, structural challenges emerged that significantly influenced its trajectory. One critical issue was conceptual ambiguity surrounding its definition. This wasn’t merely a disagreement, it was an identity crisis that derailed strategy, budgeting, and ultimately deliverables.

In technical discourse, a distinction exists between a "national" operating system (built from scratch with proprietary kernel ownership) and a "localized" operating system (customized adaptations of existing platforms like Linux distributions). While developing a national OS requires extensive research over years and substantial investment in manpower and resources, localized systems adopt pragmatic approaches tailored to regional needs, such as full Persian-language support or compatibility with local hardware.

Iran's project leaned toward localization but carried the ambitious branding - and funding - of a "national" initiative. Critics questioned how adapting Western-designed components like kernels could qualify as creating something truly national. This lack of clarity led to resource fragmentation across multiple projects with divergent goals.

Early academic outputs like Sharif University's "Shabdix" OS or Data Processing Company's "KarAmand" exemplified this fragmented approach. Experts observed these efforts lacked clear business plans and relied heavily on transient student teams focused more on theoretical exploration than market viability. Consequently, neither project gained widespread adoption or practical application.

The "Xamin" Operating System

By 2012, amid growing infrastructure demands, Iran introduced its most prominent government-backed product: "Xamin." Unlike public expectations for a Windows alternative, Xamin targeted specialized server applications using virtualization technology. Supported by Iran’s IT Organization and Civil Defense Organization for critical infrastructures like data centers and national networks, Xamin represented success within narrowly defined parameters, but fell far short of replacing mainstream desktop operating systems.

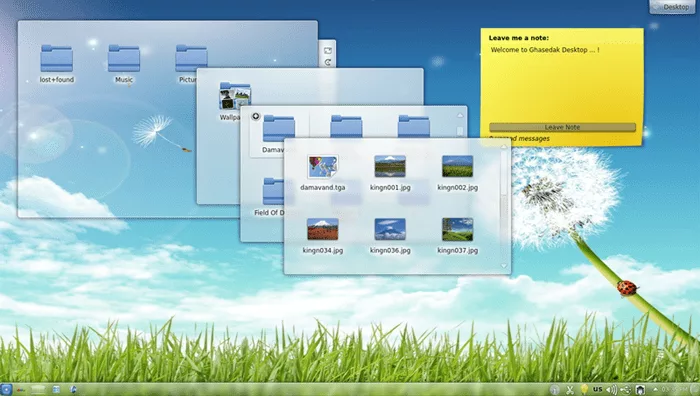

Private sector initiatives also emerged during this period with contrasting approaches. Companies such as Qasedak adopted market-driven strategies emphasizing customer-focused solutions rather than broad governmental mandates. Meanwhile, projects like Pars OS in Isfahan added further diversity but struggled against systemic inefficiencies caused by fragmented priorities across various teams.

A Legacy Marked by Missed Opportunities

From 2013 onward came additional attempts - including Homa (government-focused), Sina (security-centric), Pars Linux (user experience-oriented), and IranNix (high-security) - but none managed to overcome longstanding issues like resource dispersion or lack of unified vision.

By 2021-2022 discussions resurfaced about reviving domestic OS development under scaled-down ambitions described as modular "basic services." Simultaneously bold claims emerged regarding artificial intelligence-focused systems, a pivot raising questions about feasibility given prior setbacks in simpler projects.

Ultimately whether these new paths yield meaningful results remains uncertain amidst echoes from past failures.